From electronic textbooks to online documents that multiple students can view and edit simultaneously, the academic experience has changed drastically from the days of typewriters and volumes of library reference books. With university administrators, faculty and students on the lookout for ways to maximize the collegiate academic experience, online tools such as Quizlet, access to programs like Stata and Qualtrics, subscriptions to journals and even live video-conferencing tools are made available to the student body.

However, while the widespread adoption of these changes have enhanced the learning experience for all students, there does exist one advancement that remains limited to a small, but growing, group of students: “study medication.” Prescribed to individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), the medication, while still used by some as an everyday solution to hyperactivity, has become what is referred to as a “study aid” by students aiming to improve academic performance, manage stress and, at at times, increase endurance for a long day of partying.

Interested in the usage of these medications on campus, The Brandeis Hoot Features section conducted a survey and series of six interviews with students on the topic. Based on the 250 responses submitted anonymously, it became clear that, while the survey may not have been widespread enough to be statistically significant, the results were significant enough to determine that student use of ADHD medication, legally and illegally, is prevalent on campus.

Of the respondents, 15 percent use some form of “study medication,” the most common being Adderall (33 percent), Concerta (21 percent) and Ritalin (18 percent). Fifty-seven percent of these students have prescriptions, and 44 percent of the respondents who use medication indicate using the medication daily for normal functioning. Thus, it becomes likely that there exist some students with prescriptions who do not need or use the medication for the purposes of managing ADHD, but there also exists a substantial percentage of users without prescriptions at all (42 percent).

One interview subject, a senior at Brandeis, explained he got his prescription junior year of high school to help with the standardized college admissions tests. “It was prescribed, but I never actually went and saw a doctor. My dad just called and they just wrote the prescription for me,” the student explained.

This introduction to the medication during the high school standardized testing period was not uncommon. Another interview subject shared a similar story. “I took it every time I took the SAT. So like, two or three times in high school.” However, unlike the student whose father was able to obtain a prescription for him, this student was able to get the drug from a high school friend with a prescription.

Of the Brandeis students who use the medication, 58 percent began using before they arrived on the college campus. Yet while 90 percent of the pre-college users have prescriptions, only two-thirds of those pre-college prescribed students indicated using the medication for everyday functioning. The other third indicated that they obtained prescriptions for standardized exams, as the student mentioned above, or for performing better in school.

Unlike the students who began using prior to their time at Brandeis, 80 percent of students who started using once at Brandeis are unprescribed. “A lot of people I know have used it or tried it at least once,” one student explained. “I definitely suggest it to those who have not,” the student stated while explaining that usage recommendation spreads by word of mouth.

Consistent with the interview, the survey data showed that when asked, “What factors led you to start using the medications?” 47 percent of students responded “a peer or friend suggested I try it.” Hearing about it via word of mouth, seeing a peer or friend use it and being recommended to try it by a psychiatrist all tied at 13 percent as the next most popular answer.

“A friend told me about … Modafinil, and so I use that, and it helped me get the focus I needed,” said one student who explained having not used any medication until his fourth semester of college when introduced to the medication by a friend.

Aside from the prescribed, daily users, eight percent of students indicated they use the medication weekly, while 47 percent recorded using the medication on a semesterly basis. “I already have pretty good focus and work ethic. It kind of just [gives] me that extra push if I [have] multiple papers due at the same time or exams, midterms, finals,” said one student in an interview.

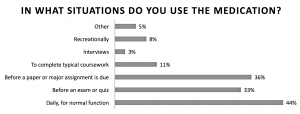

When asked “In what situations do you use the medication?” students selected “before an exam or quiz” and “before a paper or major assignment is due” as the two most common situations. In written survey responses, students used words such as “higher concentration,” “focus” and “less stress/anxiety” as principal reasons for using the medication.

One student who pays a student-dealer for medication stated in the survey, “Honestly, I hate to say this, but it has made my anxiety during high-stress times manageable. During midterm season and finals when I might have multiple papers, presentations and exams in a few-day period, taking Adderall has not only helped me complete the assignment, but has saved my mental health. I wish I didn’t take it, but without it I am paralyzed by anxiety in high-stress periods.”

These sentiments are consistent among many of the “semesterly” users. “I kind of regret being dependent on it now during exam periods,” explained a student during an interview. “I just feel like when there’s exams coming up or I have a really big paper to write, I just feel like I won’t be able to get it done unless I take Adderall or Ritalin or whatever. It’s just like, I feel like I need it. I feel like it’s going to help put me in the zone to be productive, and without it I won’t be able to finish whatever I have.”

Another student explained that the medication allows for extreme focus, even on assignments that may be uninteresting. “I honestly give credit to the study medication I have taken over my collegiate years to my success in and outside the classroom,” the student stated. In addition to using the medication to perform academically, the student has found the medication to be beneficial recreationally, invoking an “invincible” feeling. “Whether it is out at a party or even for an interview … my confidence goes through the roof, and I believe I can talk to anyone about anything on it and sound intelligent.”

While the medication seems to have had positive impacts for many of these students, using does not come without side effects, according to a few students interviewed. “I don’t really like how it makes me feel when I take it, so I try to take it as [seldom] as possible,” explained one student.

The most commonly noted side effects include an inability to eat and an extraordinary feeling of exhaustion as the medication wears off. “Sometimes I feel pretty drained sleeping wise,” said one student who schedules his medication usage to ensure he will want to go to bed by the time it wears off. Other less common side effects include excessive sweating and dry mouth, according to a student interviewed.

While many survey respondents cited side effects as a reason to not take the medication, one student interviewed, a Brandeis athlete, stated that throughout his time he has confidently known “over 100 people in my friend circle” who used the medication. “More athletes used it compared to just the kids who didn’t really play a sport or aren’t necessarily involved as much. I don’t know the reasoning behind that … maybe because they had more time to study and we didn’t and so you’d kind of cram and get on study medication and just kind of stay up all night,” he explained.

The going rate for medication ranges from $5-10 per pill depending on the number of milligrams in the pill, 20 milligrams being the typical dosage size. However, each interview subject stated independently that more often than not, their friends give them the medication for free, or they give their own medication away for free.

“I’ve always done it off a friend … a good amount of them are prescribed so I’ve just always went to them. Most of the time honestly they give it to me for free. I don’t really pay for it. I’ve only ever paid if I want a lot for a finals week or something. But usually, it’s just friendly,” said one student.

It is not surprising that students cited their friends with prescriptions as suppliers given the influx of students registered with Academic Services over the last 10 years. “I started here in 2005, and we had 120 students register with this office. We now have 450 registered with the office,” said Beth Rodgers-Kay, director of Student Accessibility Support, or as it was formally called, Disabilities Services and Support.

While not all of the registered students have attention deficit disorder (ADD) or ADHD, Rodgers-Kay approximates it is a majority. “We’ve had a couple of other diagnostic areas increasing though, so I would say … 85 [percent] of the students registered with us have ADD,” she stated.

Having worked at Brandeis for over a decade, and in this field for over 30 years, Rodgers-Kay believes there are multiple reasons for the increase in ADD and ADHD diagnoses. “I’m pretty sure some people are prescribed ADD meds who don’t even have ADD,” she stated. However, she believes that a decrease in the stigma associated with the disorder and an increase in accessibility of the field contribute to the increase in diagnosis as well.

“The field of diagnosing ADHD and other conditions … is increasing in nuance and sophistication,” she stated. With each decade, the lumping of conditions under the umbrella of ADD and ADHD is being broken down. Because many conditions can seem like they have the same manifestations as ADHD, students are oftentimes misdiagnosed. “A positive direction would be increasing the sophistication about when somebody is struggling and it seems like they are underachieving, let’s actually really get to the bottom of what’s going on and not just too quickly give it a name,” Rodgers-Kay said.

In one case, Rodgers-Kay worked with a student who had been taking a cocktail of about 12 different medications diagnosed by different doctors. Worried about how the different medications were interacting with each other, she shared her concerns with the student, who was ultimately scaled back to one medication. “She became more effective when she scaled back,” Rodgers-Kay explained.

The perception by many students, especially undiagnosed students using the medication on a case-by-case basis to study for exams or write papers, is that all ADD and ADHD medication are stimulants. Yet according to Rodgers-Kay, only about 40 percent of the students registered as having ADD or ADHD use stimulant medication, while 40 percent use a combination of antidepressants and the last 20 percent of students is unmedicated.

“There’s also a comorbidity where some students with ADD also have some depression or also have some anxiety, so that’s why when they’re working with a doctor or psychopharmacologist they’re really looking at what’s the best combination of meds,” she explained. Because the prescription and subsequent response to the medication vary depending on the student, it is important the diagnosis is right.

Students can have the disorder with and without hyperactivity, explained Rodgers-Kay. Depending on what the exact diagnosis is, the symptoms can vary.

One student with a prescription to Concerta and Ritalin expressed frustration with the term “study medication,” as it implies “these aren’t prescription medications that individuals take to deal with neurological conditions, especially ADHD,” she wrote in the survey response. The student noted that she depends on the medication to manage her ADHD symptoms, which means allowing her to choose what she focuses on.

Another student with prescriptions for Vyvanse and Concerta stated the medications allow her to achieve grades that reflect her “actual intellect.” She continued, “I do not take it as study medication. I take it every day.” When asked what impact the use of study medication had on students, responses such as it “has allowed me to be more successful/reach my potential in my courses” were common from students with a diagnosis and prescription.

While qualifying for accommodations such as extra time on exams and notetakers requires a neuropsychological evaluation, Rodgers-Kay explained that what makes the difference for many students with ADHD is looking at how they set up their routines and their habits. “Maybe they start everything, but they have trouble finishing,” she said as an example of a challenge a student with ADHD may face. “Ultimately, the goal for our work with students is not to help them lose the diagnosis, but rather to learn to manage it,” Rodgers-Kay said.

As students with a diagnosis use medication to function at their highest potential, survey results and student interviews brought to light the fact these medications have reached far beyond those with ADD or ADHD.

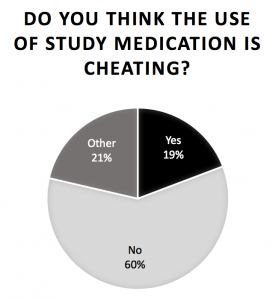

“I think it definitely gives you an edge and might consider it unfair, but I think that if it’s there to be used and it helps, then you’re doing yourself a disservice not to use it,” stated an un-diagnosed student user. “It’s kind of messed up, and it might not be the most healthy thing, but if I get As on my midterms and finals, I’m going to take it.” This student’s mindset is far from an anomaly.