At the beginning of the semester, The Brandeis Hoot Features Section put together of a list of questions we had about the Brandeis community. One question we felt particularly passionate about was whether or not a diversity of political ideas exists on campus. Because we so rarely hear more than “one side” of any argument in our daily lives at Brandeis, we decided the topic warranted an investigation.

Two weeks ago, we collected responses to a three-question poll asking students how they politically identified, their comfort level sharing political views on campus and why they hesitated to share views, if at all.

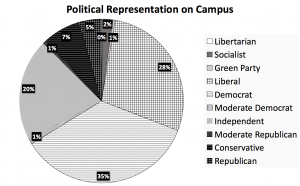

Based on 509 responses submitted anonymously from current Brandeis undergraduate students, we concluded that while about 64 percent of the students identify as some degree of a Democrat or liberal, 20 percent consider themselves independents and 13 percent identify as some degree of Republican or conservative.

So if there is indeed a diversity of political opinions on campus, are students not sharing their opinions? According to the poll results, the answer to this is yes. Further, there exist correlations between how likely students are to express their opinions and how they politically identify, as well as why students hesitate to share opinions and how they politically identify.

Poll results were collected in various locations across campus, including the Goldfarb Library, Shapiro Campus Center and the Admissions bus stop. Polls were also distributed to groups of athletes, in a few classrooms, including two journalism classes, a politics class and a sociology class as well as posted on various Facebook pages.

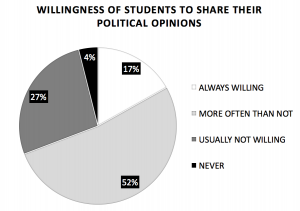

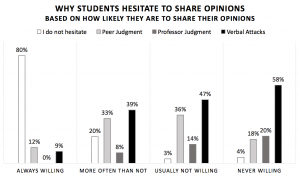

The “Willingness of Students to Share their Political Opinions” graph makes it clear that there is a large percentage of the student body that does not always feel comfortable sharing their political opinions on campus—a concern for an academic institution that encourages open dialogue among its students.

While 69 percent of the student body will more often than not, if not always, share their opinions, 27 percent of the student body usually will not share and four percent of the student body never shares, according to the poll.

To further break down this data, the correlation between the willingness of students to express political opinions and their political identifications was examined.

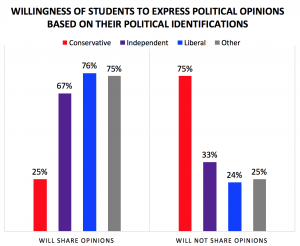

The main focus of the “Willingness of Students to Express Political Opinions Based on Their Political Identifications” chart was to determine if there was, indeed, a correlation between how students politically identify and how willing they are to share opinions.

Specifically, we wanted to explore whether conservative students were less willing to share their opinions than students who had a more liberal identification, or an identification outside of traditional party lines.

In the collected data, students were asked to politically self-identify. While responses varied greatly, including responses such as “liberal/Democrat-ish (not too extreme)” and “conservative independent,” they were categorized into 10 main political groups, and four “other” categories.

The main political groups included the following: libertarian, socialist, Green Party, liberal, Democrat, moderate Democrat, independent, moderate Republican, conservative and Republican. The non-political groups included international, other, do not know enough to identify and do not have a political identification.

From these 14-category responses, anyone who identified as “conservative,” “Republican” or “moderate Republican” was put into the “conservative” category. Students who identified as “liberal,” “Democrat” or “moderate Democrat” were put into the “liberal” category. “Independents” maintained their own category, and all other political identifications were put into the “other” category.

The “Willingness of Students to Express Political Opinions Based on Their Political Identifications” chart summaries the data. Twenty-five percent of conservative students were willing to share their opinions, and 75 percent were not willing to share their opinions on campus. These responses are drastically different from those of “liberal” and “other” students who will share their opinions 75 percent of the time and keep quiet only 25 percent of the time.

It is notable that while students who identified as “independent” were willing to share 67 percent of the time—significantly more than conservative students—they were almost 10 percent more likely to not share than “liberals” and “other” students.

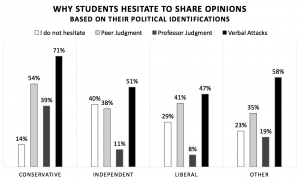

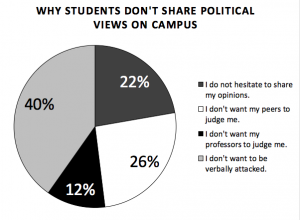

To further explore this, we asked students why they don’t share their opinions on campus. The provided response options included: “I don’t want my peers to judge me,” “I don’t want my professors to judge me,” “I don’t want to be verbally attacked” and “I do not hesitate to share my opinions.” Students also had the option of writing in their own responses.

When we correlated student political affiliations with why students hesitated to share opinions, a few different trends became apparent.

Conservative students are significantly more likely to be concerned about judgment from their professors than their more liberal peers, while being the least likely group to respond that they “do not hesitate” to share opinions. Additionally, all students, especially conservative students, are concerned about being verbally attacked.

In a similar analysis looking at why students are hesitant to share opinions depending on willingness to share, it is clear that as students become less and less willing to share, they are increasingly concerned about verbal attacks and being judged by their professors and less concerned about judgment from peers.

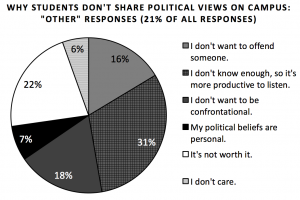

While peer judgment, professor judgment and verbal attacks were all provided as possible responses for students, 21 percent of students wrote in their own responses in the “other” category. Within these responses, there were many common themes.

The most common “other” response, with 31 percent of students who wrote in responses answering this way, was some variation of “I don’t know enough, so it’s more productive to listen.” Some of these responses included statements such as, “I don’t feel like I know enough to defend my points of view.”

The second most common “other” response from 22 percent of students who wrote in responses was some variation of “I don’t want to offend someone.”

“The people on campus censor others in ways that may be too much. I never know if I’m right [or] am saying the right things. I don’t want to offend people,” wrote one student concerned about offending peers.

While 22 percent of the 20 percent of students who responded to the “other” section is small, it is significant that multiple students took the time to write that offending their peers was a major concern of theirs—one that prevented them from sharing their own opinions on campus.

Other categories that developed out of the “other” category include, “I don’t want to be confrontational,” “My political beliefs are personal,” “It’s not worth it” and “I don’t care.”

While this is just part one of data analysis, as next week’s edition will contain additional charts, commentary from Brandeis professors and continued commentary from students, this initial data is revealing of a political climate on campus that is not conducive to students sharing ideas openly.

If those with opinions most differing from the norm are too afraid to speak, how are meaningful discussions to be had? If students are concerned about being verbally attacked, how can we create an environment where students feel comfortable enough to share?

As the Features Section continues to investigate this issue, we hope the Brandeis community reflects on this data and uses it not only as a starting point to change political culture on campus, but as a conversation starter—a reason to start speaking.

Read more about the Features investigation into diversity of political ideas at Brandeis:

Diversity of Ideas Poll Results: Students Respond

Admin. urges students to speak freely

Be sure to check out next week’s edition of The Hoot for further analysis.