Financial consultant Kermit Daniel, speaking to Brandeis community members at a presentation on Thursday, Sept. 22, reported that because Brandeis is such a complex university without the size, wealth or specialties of its competitors, funding the university in a sustainable fashion has been, and continues to be, an issue for Brandeis.

“Brandeis has a structural imbalance in its financial situation,” said Daniel. “This situation arises because Brandeis is a complicated university, which is another way of saying Brandeis is an extremely ambitious university with very high standards,” he continued.

Brandeis, unlike many liberal arts colleges, not only provides its undergraduate students with a liberal arts education, but is also a top research university that offers both graduate and undergraduate courses and grants degrees in a wide range of disciplines. This requires many centers, institutes and programs associated with the university, as well as specialized resources, Daniel explained.

“What you are achieving with this university is very difficult to achieve even for very large universities and very specialized universities, and you are not specialized, and you are not large,” Daniel said. Some schools specialize in arts or engineering, for example.

Daniel has been conducting a comprehensive analysis of the financial structure of Brandeis since April 2016, when he began his work for the university, according to an email from President Ron Liebowitz last week. He is a consultant from the firm Incandescent.

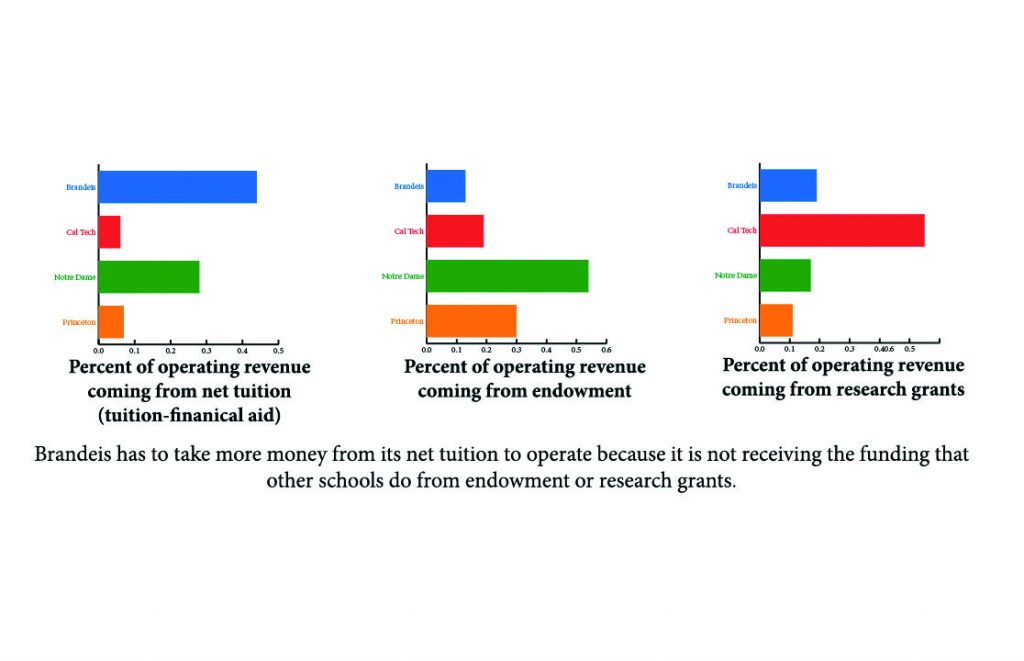

Brandeis’ peer group is not made of liberal arts colleges like Vassar and Middlebury, but rather large research universities such as Duke and Princeton. Brandeis is the smallest competitive research university in the country. Only the California Institute of Technology (Cal Tech) is smaller. Because these institutions are more specialized, they are able to get more funds from their research than Brandeis. Brandeis produces equally impressive research and degrees, but it has to draw from its tuition revenue much more than its peers to cover these costs, said Daniel.

Universities’ operating revenue comes from a variety of sources, including net tuition (tuition minus financial aid), endowment returns, research grants, gifts and others. According to Daniel, 54 percent of Princeton’s operating revenue comes from its endowment, as it is a “rich” university. Twenty-eight percent of Notre Dame’s operating revenue comes from its net tuition, as it is a “large” university, and 55 percent of Cal Tech’s operating revenue, despite its small size, comes from research grants, as it is a “specialized” university.

Brandeis is not wealthy, large or specialized so its business model is different from its peer schools, said Daniel. Forty-four percent of Brandeis’ operating revenue comes from net tuition, 19 percent comes from research grants, 13 percent comes from the endowment, eight percent comes from gifts and four percent comes from other sources. Brandeis does not has as much money from either tuition, research grants or endowment as the schools listed above.

Brandeis operates on a “structural imbalance” meaning that it is doing several unsustainable things to balance its budget in the short-term. Brandeis looks like it is gaining revenue by increasing tuition, for example. However, Daniel said the school is doing several unsustainable things to balance its budget. If you factor in all the money Brandeis should be spending on items such as faculty salaries or campus maintenance, we are actually running a slight deficit, said Daniel.

Based on Brandeis’ accounting principles, we don’t see the expenses we are putting off which will hit us eventually and have an impact on the school’s total budget.

When looking at the bottom line of Brandeis, the university’s net profit or loss over the course of history, “It shows that by and large, you are running at a slight deficit,” Daniel said. “I want to focus on the biggest plus year you saw, which is 2015, and then what I’m doing is subtracting all the unsustainable practices,” he said.

In his analysis, Daniel took the bottom line from the fiscal year ending in 2015 and subtracted out the amount of money the university would have lost from its bottom line if it had not overdrawn from the university’s endowment. This amount, when calculated, ended up being $6.5 million.

Because Brandeis draws on 5.9 percent of its endowment, higher than the suggested ceiling of 5.0 percent, it makes it much more difficult for the endowment to grow, Daniel said. Taking into consideration low-market return and inflation, at times Brandeis might even draw more from the endowment that its return, meaning the endowment would not be growing at all.

The $6.5 million represents the amount of money Brandeis was able to add to its bottom line and use simply because it took a higher percentage of money from its endowment than what is sustainable.

Daniel additionally subtracted $1.5 million and $5 million to compensate for underpaid faculty and staff. While these numbers are rough estimates using the AAU median salaries as a point of comparison and are by no means exact, they represent other areas in which Brandeis is not accounting for the money it should be spending.

Deferred physical plant maintenance and IT maintenance was another expense Daniel subtracted from the bottom line of the university. Because for so many years Brandeis has not kept up with maintenance, the university would have to start paying $12.4 million on deferred physical maintenance and $1 million on IT maintenance annually to make up for the already existing issues, and to prevent future maintenance issues, said Daniel.

Lastly, as noted earlier, eight percent of Brandies’ operating income comes from gifts. This is not sustainable. Rather, this gift money could be put into the endowment to help it grow, not spent on annual operating expenses, explained Daniel.

“The implication of all this is that it’s especially important to be good at making decisions. This is everything from large strategic decisions that you may make once a generation, to much smaller day-to-day decisions about how to operate the university. But being able to make those decisions exceptionally well is going to be important,” Daniel said.

If all of the unsustainable practices Daniel accounted for had not occurred, Brandeis would have operated at approximately a $30 million deficit in 2015.

Some community members in the audience seemed worried about the financial stability of the university at the close of Daniel’s presentation, as evidenced by a professor who, through her question, expressed concern about her area of study losing funding because of Brandeis’ financial status.

“I just want to assure people in the room, this is not a point where we are saying … the university is bankrupt,” Provost Lisa Lynch said, addressing the “depressing” close to the presentation, as she described it.

Lynch acknowledged the university’s finances were a growing concern, but noted that they could continue on as is and even show a balanced budget from year to year under GAAP.

“The point of the analysis that Kermit has done is to show that we have a set of practices that every one of us in this room is familiar with that are just not sustainable. Every one of us that sits in a room where we have wind and rain coming into our office understands the realities of deferred maintenance,” Lynch said to an audience that had clearly experienced the effects of this deferred maintenance, as they erupted in laughter.

Lynch noted that this detailed analysis of the university is the first step to making choices that will positively impact the university’s future. “We have to make choices but make sure that those choices are evidenced based,” Lynch said. Daniel’s analysis is a vital part of this evidence.

“We have an amazingly productive university, and it’s build on good will, sweat, equity, a reasonable financial base that would be sufficient for a much less complex university, but our ambitions are well beyond our financial resources, and all of us take pride in that,” Lynch said. “That’s the sort of scrappy Brandeis character. It’s the thing we love doing.”

While Brandeis faculty, administration, staff, students and even physical buildings are pushed hard, it’s a push that can only be sustained for so long, said Lynch. “That’s what this message is about.”

Daniel’s presentation, along with designated time for questions, will happen twice more next week at the following times: Monday, Sept. 26 from 3 – 4 p.m. in Levin Ballroom and Wednesday, Sept. 28, from 8 – 9:30 p.m. in Sherman Function Hall, Hassenfeld Conference Center. These presentations are open to the community. Emily Conrad ’17 and Wil Jones ’17, the undergraduate representatives to the Board of Trustees recommended attending because the presentation is a step forward in terms of administrative transparency.

“This is a sign for a really bright future and a strong relationship with our new administration,” Conrad said in an interview. “It’s an opportunity to really learn about the basis and evidence for why our administration makes the difficult decisions it does. I think they are reaching out a hand to the community, and it’s important for students to reach back and work together if we want to have a say in the future of Brandeis.”