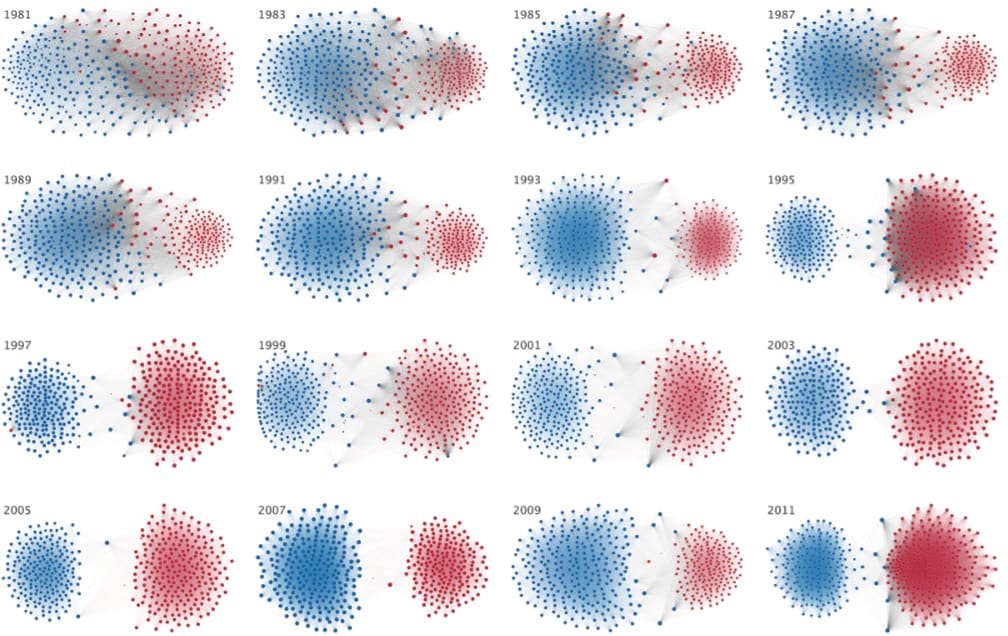

As former United States president Abraham Lincoln famously said, “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” Although the context of this speech emphasized a tumultuous time in our history, the same concept can be applied today. Our nation has divided once again, not in militarized conflict but rather in politics. We have an ideological gap that now aligns with a gap between our two biggest political parties, which is indicative of a worsening polarization. Recently, as illustrated in Figure 1, individual representatives in Congress have become less accommodating of policies passed by the opposing party.

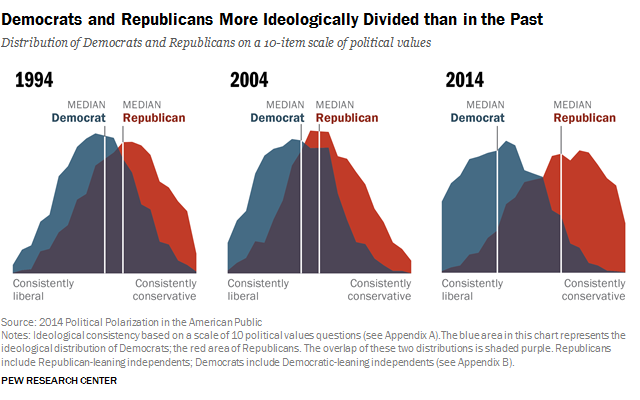

With the upcoming presidential election on Nov. 3, extreme partisanship becomes an increasingly pressing problem. If citizens of the U.S. vote solely based on party line this year, we may risk electing candidates that are not truly dedicated to representing the policies and issues we are most concerned about, thus displacing the folk theory of democracy. Even if candidates are elected based on their stance, extreme polarization means the party or ideological groups that lose the election will feel unrepresented and will be unable to come to a compromise with the party in power. Since 1994, the divide in Congress has only grown, as shown in Figure 2. If left unchecked, this vicious cycle may continue in future elections, gradually pushing each side to its poles over time.

One of the causes for polarization is psychological. Humans are naturally aversive toward outgroups, so people tend to dislike any policy that is associated with a party or ideology different from their own. This relates to the folk theory of democracy because voters will want to elect a candidate that represents their issues, not the opposing views, which inherently kindles more of the “us versus them” mentality that creates polarization.

Similarly, as geographic sorting becomes more apparent, it creates an inherent positive feedback loop of self-selected polarization. Americans tend to choose a neighborhood environment that matches our own values and beliefs, which includes political beliefs. Liberals have recently begun to move into cities with other liberals, and conservatives have done the same with areas that are heavily conservative. In some cases, neighbors even socially conform to each other’s beliefs despite beginning at different ends of the ideological spectrum.

Scholars also have studied a cause rooted in our electoral system. The modern day has shaped two parties that are more distinct than when America was founded. Historically, the parties used to overlap, change out or were similar enough to each other in ideology. Now, ideology and party identity essentially match. There are very few liberal Republicans or conservative Democrats left in the political arena. This leads voters to choose the party instead of the candidate, and compromise is less frequent in our branches of government. In other words, Duverger’s Law has come to pass. United States politics has split into a true two-party system, with no need for coalitions to obtain a majority. As such, there is even more concern for polarization because one party will always be dominant.

This problem need not plague us forever because two solutions can directly counter the causes. First, encouraging intergroup contact between the two parties may help reduce prejudice and emotion-driven motivations against the opposing party. If the groups are willing to be brought together to keep an open mind and share ideas in a mediated setting, they may find common goals. This goal is attainable, evident in Ireland’s “Citizens Assemblies,”provided as an example by Greater Good Magazine.

In order to counter the systemic cause, we may also consider restructuring our electoral system to proportional representation. This would rid Duverger’s Law and allow minority parties more representation. With more than two parties, there is less possibility of rivalry between strong, dominating parties. Proportional representation also encourages the forming of coalitions so an extreme bipolar distribution of power cannot happen. Reforming an electoral system, however, will require significant support from the public, and it is likely that only more progressive citizens will be inclined to approve of such a notable change.

In the end, basic liberties and human rights should not be politicized. Both Republicans and Democrats have “owned” certain issues for far too long. Perhaps with toleration and compromise of ideological differences from both parties, we may be able to unite our house again.